By David Farnell, (c) 2000

It was a weekday morning, but school had just let out for the summer, and as she waited in the shadow of the Popeye statue in front of City Hall, Maria Dolores Villanueva was enjoying that feeling of almost-illicit joy, free from school with three months of wonderful, bright days and bone-baking heat ahead of her. She knew from experience that she wouldn’t enjoy it as much later, that she’d be longing for school to start again after no more than a month of freedom (freedom to do extra house chores, freedom to work through the pile of summer-reading books, freedom to study the intricacies of proper Spanish under her mother’s strict eye), but she would enjoy it while she could.

The town was alive this time of day, much more than it would be when the sun beat down white-hot at noon and half the town was closed down for siesta. Over to her left, La Raza Unida had set up a table to get people registered for the upcoming presidential election. A land of agriculture, Zavala County, Texas, would solidly back Jimmy Carter.

Mothers were out shopping with their children in tow. A few old spinach farmers had business in town, their sun-crinkled faces squinting through the bug-spattered windshields of their ancient pickups. A group of scruffy Anglo kids a little older than she strutted down the street in Kiss T-shirts and tattered bell-bottoms. A big green Oldsmobile parked across the street, and the man inside brought out a map.

That attracted her attention. Crystal City might be the Spinach Capital of America, but that didn’t mean it was a big tourist draw. She knew just about all the cars in town, too, and this shiny new job wasn’t from around here. She left her backpack in Popeye’s shade (she didn’t want those sandwiches spoiling) and walked a little way to one side–yes, it was a rental, from San Antonio. Maria smiled, proud of herself. Being the Sheriff’s daughter had rubbed off on her, and she never hesitated to pursue a mystery. Now here was one to kill the time until Danny and Loi arrived.

The man got out of the car. At first, Maria thought he was Chicano, but after studying his face (he was craning his head around, looking for something), she pegged him as Asian. Not many Asians in Crystal City. Maybe he was a relative of Loi’s, although he didn’t look much like him. His face was deeply tanned, and deeply lined, and beneath his out-of-date fedora his hair looked like it would be mostly gray. He wore a business suit.

She thought for a moment, then checked for traffic and crossed the street, coming to a stop a few feet behind him. She watched him checking the map again, then messed with her wavy hair–when she’d turned thirteen last month, she’d decided barrettes were for kids, and was trying to cultivate a wild, devil-may-care look, with the hair flopping over one eye like most of the women in Starblazers–and cleared her throat theatrically, her hands clasped politely behind her back.

He looked around, his face neutral. She looked in his eyes and felt the day turn cold. Just for a second, she felt she recognized him, that they were somehow family, and that he had seen and done things best forgotten, and that somehow these were things she would do, too, one day. Something had passed between them, and in future years, she would think of that moment many times, as she later realized that this was the turning point; this was where she had started down the path.

The moment passed, the morning’s low-oven heat returned. She forced a smile and said, with only a trace of border accent, “Hello, mister. Um, may I help you find something? You look new in town.”

He just looked at her for a moment, and it occurred to her that perhaps he had felt the same chill as she. Then he blinked and smiled–it was a nice smile, a little sad–and said, “Thank you, that’s kind of you. Actually, I’m looking for the school. I’m not sure which one, really, but maybe it’s yours….”

“Maria.” She held out her hand confidently. “Maria Villanueva. I’m pleased to meet you.”

Although it had disturbed her, the feeling of connection with him nonetheless let them pass quickly through the stages of polite introductions to a more relaxed, voluble state of near-friendship. His name, he said, was Henry, “You can call me Hank, though.” His voice was entirely American, maybe Californian, she thought, without enough experience to be sure. Educated, but relaxed. His hands were not those of a farmer, but they weren’t soft, either. He was obviously quite fit, and she couldn’t quite place his age, but she thought he might be as old as her father, which would be the mid-fifties. She told him about the three schools in town and circled them on her map before asking what had brought him to a little Texas border town.

“Oh, just…memories, I guess.”

“Did you live here before?” She sounded incredulous.

“Well, sort of.” He paused, considering, then seemed to make an uncomfortable decision. “One of the schools, I can’t remember which one and the reports are dam–darned unclear, used to be on the land where my parents and I stayed awhile. Did you ever hear of Crystal City Internment Camp?” He cocked his head slightly, eyes narrowed–perhaps he expected it to have been forgotten, covered up like an old garbage dump.

She thought a moment, then nodded. “You mean the old prison camp, during World War Two, right?” He nodded back. “They kept Japanese and Germans and some Italians there. And you were put in there, even though you were just a kid? My father told me about it.”

He smiled. “I’m a little older than that, actually. But yeah, I was there. Not long, though. I volunteered to join the Army, so they let me go fight the Japanese.”

“But you’re Japanese!”

“Nope. American, born and bred. But I grew up speaking Japanese in the house, and then I studied Asian languages and cultures in university, so they made me an interpreter. I used this–” he tapped the side of his head “–not a gun, to fight. Well, most of the time.” A cloud passed over his face, some memory almost surfacing, then he smiled and sat on the hood of the car. “Anyway, I was in San Antonio on business and decided to come take a look. So that’s my tale of woe. What’s yours?”

She smiled back. She liked how he talked to her, as if she were older, as if they were long-time friends. Like her father, never treating her like a child. She leaned against the car, next to him. “There’s not much to tell. My father is the Sheriff, so I don’t have as much freedom as other kids, and my mother, she’s from Mexico, so she’s a little old-fashioned. But it’s OK. Father was in the War, too–in Europe, though. My brother is going to join the Army, too, with his best friend, after they finish university at A&M. They want to be Airborne. They’ve just graduated high school. And tonight we’re going camping at the lake–” She broke off. What did I tell him that for? she thought. What if he’s a pervert, and follows us out there? “Um, all of us, Father, Mother, Danny, and me. And Loi, that’s Danny’s friend.” There. He wouldn’t try anything if he thought the Sheriff was with them.

But she could see that he’d noticed her withdrawal, and she felt bad for not trusting him. Not too bad, though. Her father had raised her to be friendly to strangers, but not to trust anyone who hadn’t earned it.

They wrapped it up pleasantly, and she showed him where the Compean Cafe and a couple of hotels were, and he took his leave just as Danny and Loi drove up in Danny’s old Mustang.

As she crossed the street he called from the car, “Maria?” She turned. “I almost forgot. Have you…have you seen any strangers around town lately? Other than me, I mean?” He grinned.

She thought about it, then shook her head. “No. Nobody I can think of. Why?” This was getting more interesting. Was he some kind of policeman?

But he answered in just the way an undercover cop would. “Nothing, really. You take care, now.” And with that he drove away, and she turned and ran to the entreaties of her camping partners.

***

Maria threw her bag to Loi, who caught it one-handed through the passenger window with a laugh and tossed it in the back. She grinned at him, desperately wishing he were younger, she were older, that he wasn’t her brother’s best friend, that he would notice her changing body.

Loi got out of the car and folded the seat forward to let her in. He used to offer to sit in the back, but she’d always refused–it was ridiculous to imagine Loi, taller even than Danny, trying to fold himself into the back of the little muscle car. It was quite roomy for her. Of course, if Loi could only join her…she shivered with the memory of a vivid dream, she and Loi in the back of the car, Danny driving up front, whistling and looking back at them in the mirror, grinning as they went at it.

Life at thirteen was very, very weird.

“Hola, Loi,” she greeted him, as she eased past him into the back of the car. He smiled–he almost always smiled, a real smile of honest, irrepressible joy that he seemed to draw from everything around him–and said “Hey, Maria” back to her. He towered over her, tall and rail thin, but muscular from a hard life and hours of basketball with Danny, his skin a dark brown from the powerful Texas sun, almond eyes a strange light brown, arrestingly odd in his Asian face. His bright teeth stood out in that face, and his black hair, cut unfashionably short, spiked up all over his head.

“Come on, let’s go!” crowed Danny. He was Loi’s height, but more filled out, more solid and strong. He’d been a small kid, a late bloomer, and had endured more than just the usual taunts of “wetback” and “beaner” from the Anglos at school. After his father was elected Sheriff, it went underground, but got even worse. Danny had retreated into books and become a straight-A student, which of course just provided more fuel for the bullying, but when he put in a last, huge spurt of growth at the end of puberty, and supplemented it with an intense regimen of exercise, the bullying had stopped. In his senior year, Danny had been the young god of the high school: captain of the football team, forward on the basketball team, and finally valedictorian.

It had been neck and neck between Danny and Loi, a strange, cooperative competition, as they had helped shore up each other’s weaknesses for the last two years. Loi had arrived with his family, refugees from Vietnam, going from the ruling class, to hollow-eyed victims, to new immigrants lost in an alien land, to mildly successful shopkeepers, in the space of seven years. Loi, shy and not a bit dazed, had appeared in school and immediately become the target of crude violence and more subtle cruelty, until Daniel Villanueva, the former target, had stepped in. It could have turned into an unbalanced tough guy/little geek relationship, devoid of real friendship, but Loi and Danny had proven to be complementary, Loi polishing Danny’s skills in math and the sciences, Danny boosting Loi’s English and history skills, and getting him involved with sports. And it had turned out that Loi could handle the physical brutality of the bullyboys quite effectively. He’d learned how in harder places than the Zavala County Independent School District.

So they were off on the what Danny had named the Annual Lake Espantosa Monster-Hunting Campout, a holdover from the days when Maria and Danny and their parents would camp out every summer, and Papa would tell ghost stories at the campfire, tales of Old Red-Eye, the Spanish wagon train, the ghost of Dolores (whom he had named her after), and others, some of them traditional, others he’d made up himself, and some from the stories he read in beat-up paperbacks. Danny and Maria had moaned in delicious terror, and then laughed themselves silly with sheer nervousness and shared fear in the tents late at night. Even their mother loved a good ghost story, although she sometimes admonished her husband not to scare the children too much. Later, the children had had their turn telling stories, developing a facility with it under their father’s encouragement. Mama would rarely take a turn, but when she did, it was guaranteed to be something particularly weird, from Old Mexico.

For the past four years, the tradition had changed. Dad’s back was terribly stiff–he’d been in a car chase back in his post-war days as a Texas Ranger, and had wiped out into a telephone pole. His injuries had been so bad that he’d retired from the Rangers, but his determination got him back on his feet, and he’d been elected Sheriff of Zavala County and had held the post for the last ten years. But he’d married late, and he was now in his fifties, and sleeping on the ground just wasn’t in the cards anymore. So Danny and Maria had started going it alone, and loved it. This was the second year they were bringing Loi along–and perhaps, the final year of the tradition.

They drove out of town under the growing heat of the summer sun, fields of spinach and onions and other crops rolling by. A roadrunner tried to race them for a few seconds, then gave up and went in search of snakes. Loi laughed at how little the bird resembled the one from the cartoons.

“Hey,” he said, “you remember last year, those coyotes that came howling around the camp? That was so cool!”

“You remember that one, sounded like it was crazy or something?” Danny said. “It sounded like half-coyote, half-hyena.”

Soon they were at the parking area for the lake. Lake Espantosa was not popular with fishermen–it was weedy and full of snags and snapping turtles. In fact, it wasn’t a great place to camp, either. But what drew them was the legends surrounding the place.

“You know,” Danny said, as they unloaded the car, “if we don’t find the Lake Monster this year, we may have to call off the search.”

Maria grunted, her accent stronger and words more relaxed and playful than with the stranger, Hank. “Yeah, you guys just gotta go off and be Aggies, and play Army with your Rotzy buddies. How come you don’t just settle down and be spinach farmers?” Danny and Loi laughed with her. She struggled to shrug on her backpack, stretching her shoulders back and thrusting her chest forward. She caught Loi’s eyes hovering for a moment on her chest, then looking away to focus on nothing. She thought, Hey, did he just…otice something? She felt heat blossom in her face.

Loi hefted his pack, then said, “Well, I guess we could join the Navy,” and with that launched into “Popeye the Sailor Man,” bringing groans and laughs from Danny and Maria. Loi was the only person in Crystal City, other than the Mayor, who seemed to be proud of living in the Spinach Capital of America. And so they started hiking to their favorite campsite, singing verse after increasingly ribald verse of the song, including some really nasty bits in Spanish taught to them by a dissolute uncle.

***

There was something odd about the campsite. There always had been, for they’d chosen it because of the ominous, man-high, lumpy, vaguely draconic boulder which Danny had long ago (before Maria was born) declared to be the fossilized remains of the Lake Monster, the thing “much larger than an alligator” which had dragged an unnamed Spanish woman to her watery doom in 1750, and perhaps eaten an entire treasure-laden wagon train. But this was something else. For one thing, it had been used recently. The fire-pit, which the Villanueva family had built inside a ring of rocks, was full of fresh ashes and cigarette butts. Danny thought it might have been in use only the night before. This in itself was strange, as the site was actually quite difficult to get to, involving off-trail walking, climbing a small cliff, wading through a stream, and other impediments, and almost never had any visitors this early in the season.

But odder still was the rock-and-mud castle down at the edge of the water. There was no sandy beach here–another reason the site was unpopular–but someone had found the urge to build a castle irresistable. The trio exclaimed at its fabulous intricacy, for it was a fairy castle despite its crude materials. It was over six feet square, and the twig-and-scrap-paper flag on the central tower was as tall as Maria’s waist. It had seven buildings in total, with walls, paths, and moats surrounding and snaking between them. There were even some elevated corridors linking the towers, with twigs for scaffolding to prevent their collapse. The architecture did not much recall European castles; rather, it conjured tales of Arabian heroes living in splendor and battling evil djinn and ghouls and filthy Crusaders, for it made good use of three small boulders as “landscape” to make it into a mountain fastness. But there was something wholly alien about it as well, something that called to mind Burroughs’ Mars more than anything from history.

Parts of it were already dry and crumbling, and it was obvious that despite its being above the tide line, it would soon be mere ruins. But the outer parts (for the artist must have built the inner parts first, or his arms wouldn’t have been able to reach the center) were still damp and strong. A little disturbing but not wholly unexpected was something pointed out by Loi: there were no children’s footprints around the castle. In fact, there was only one set of prints, beaten old boots, with an obvious hole in the left one. The same prints were up by the fire pit. Whoever had camped here had been alone. And large–the boots were about size thirteen, and he looked to have been rather heavy.

What sort of person would build an intricate castle in a secluded place, alone, without it being a game to play with his children? And the prints–they pointed in all directions, and sometimes swirled into circles. Loi and Danny had learned much about tracks in Eagle Scouts and on hunting trips with Danny’s father, and they agreed that it looked like the camper had been dancing around the campsite and at the water’s edge. He must have been a sight, and quite drunk, too, for they found several empty bottles of cheap wine mixed with tin cans in a surprisingly neat pile of unburnable garbage a little way into the woods.

At first, they felt a little worried about camping here, but as the stranger’s tent and other possessions were gone, it was obvious he wasn’t coming back. And although it was all a bit unsettling, it was also rather fascinating, and the whole point of the campout was to confront the weird. Danny argued that this made it all the better, and Maria and Loi soon agreed that the mystery added greatly to the atmosphere of what was, probably, the last time they would be together like this.

So they dumped their packs and went down to the water’s edge. The day’s heat was coming on in palpable waves, and they all wanted a swim. Danny and Loi were wearing cut-off shorts that doubled as bathing trunks, so they had merely to strip off their shirts and kick off their shoes before they were ready to take a dip in the chill waters. Maria had her suit on under her sleeveless blouse and moderately-flared bell-bottoms. She felt a fluttering in her chest and stomach as she began undressing. Always before, she’d worn a demure one-piece bathing suit, but today she had put on something she’d bought secretly, something she hadn’t wanted her mother to know about. Now she didn’t want Danny to see it, for despite their unusual closeness in defiance of conventional walls of age and gender, he was still in this situation a sort of father-substitute. And Loi–oh, she wanted him to see it, very much so; she’d bought it with him in mind. But she was felt a keen edge of terror to her desire.

Still, she couldn’t stand there looking like an idiot. Her face burning, she quickly stripped off her outer clothes to reveal a pale-blue bikini, the color chosen because she’d thought that it nicely set off her brown skin. It was not, by the fashions of the disco decade, overly revealing–in fact, on the beaches of any cosmopolitan area it would have been considered quite unremarkable. But this was deep West Texas, and she was their “little hermana,” by blood and choice, and Danny and Loi stopped goofing around in the water and became quiet. Maria didn’t look at them at all; she simply strode into the water and slipped under, then surfaced and started swimming. She didn’t want to see their expressions. She tried to pretend she was completely alone in the world.

Soon the awkwardness passed, and Danny splashed her, and the three of them erased their discomfort in play. But there was still a new distance, and Maria noticed that the young men didn’t tickle or wrestle with her as much as they had in the past.

She was struck, as she had often been in recent days, that everything was changing rapidly. It gave her a hollow feeling that she tried to ignore.

Later, Danny called out to her, “Hey, Maria, come here!” He was squatting shirtless before the castle, straining to peer into the center building, with its yard-high tower. As Maria came out of the water and walked up behind him, she looked at his droplet-glistening body, the athletic muscles of his back and legs shifting beneath his dark, smooth skin, and thought wryly, If that boy wasn’t my brother…then stopped still and closed her eyes, scolding herself, God, Maria, you’re turning into some kind of puta! What’s wrong with you?

She shuddered and opened her eyes, then went up to her brother and squatted beside him. “What is it?”

“Take a look at this, kid,” he said, pointing at the roof of the central building. One corner had crumbled under the punishing sun. Soon, the whole tower would probably collapse. She wished they’d brought a camera. Then she gasped, for she could see that, inside the building, there were tiny figurines, painted, perhaps made of metal.

“What is that?” she whispered. It was nearly a yard away from the outer walls, too far away to see details, and it was hard to get a good angle to see inside.

“Don’t know, but I thought, maybe with your small feet, you could creep in between the buildings and get a better look.” He grinned at her.

“Oh, right,” she said, still whispering, “so now I’m Godzilla?”

“More like Attack of the 50-Foot Chicana.”

“Oh, hah-hah,” she said dryly.

Loi came up to them, pulling on his shirt. “What’s up?”

“There’s some kind of toys or something in that middle building. Maria’s gonna go in and check it out.”

Loi grinned. “Gulliver’s Travels. Beware Lilliputians with bows.”

“You guys are a barrel of laughs, you know that?” She stood and, after studying the layout of the sculpture from other angles, carefully stepped into it. By twisting her thin, still childishly flexible body, she could place her feet on the paths between the buildings. It was like a game of Twister. She needed to take her steps in just the right order, or she would overbalance and fall, doing Godzilla-like damage to the complex. Being short helped, as her center of gravity was low, and the boys held their hands out toward her, so that she would have something to grab in case she started to fall. At first they tried to coach her, but she soon told them to be silent, as they were ruining her concentration.

She and Danny used to watch Kung Fu Theater every Sunday afternoon, when the choice was between that and mind-numbing religious programs. She would take Flying Shaolin Monkey Fist over Jerry Falwell any day. As she stepped through the castle complex, she thought of one movie in which the student had had to step from post to post in a bizarre pattern, risking a painful fall several feet to the ground if he made a single mistake. It had later turned out that this pattern taught him an intricate combat dance, which allowed him to defeat the generic bad guy. She felt like that now. Not only did she have to step carefully; she sometimes had to twist around 180 or even 270 degrees before placing her next step, and even at times move away from the center castle in order to safely approach it.

It was a dance and a puzzle. And somehow, inexplicably, it clicked in her head. Her body began to move as if it were a ballet she’d been practicing for years. As if invisible strings were controlling her limbs. She spun and twisted through the city with increasing speed, no longer caring about the destination, but glorying in her sudden, strange ability to follow the pattern. Her recent growth spurt, her developing breasts and widening hips, had left her unbalanced and awkward as she grew faster than she could adjust. But for just a moment, little more than thirty seconds, really, she felt like a celestial dancer. She understood what the hippie gurus in the movies meant about being “in tune with the universe.”

Then it was over. She was on all fours, in one of those ridiculous Twister positions, arms intersecting, one leg cocked and barely missing knocking over a tower, the other jutting out straight to her right, going down a serpentine avenue, the leg just skinny enough to fit without damage to the structures. Wet ringlets of hair hung wild before her face.

She saw with regret that she had knocked over part of a wall in her dance. It had not been perfect after all.

But her face was right in front of the crumbled part of the central building. She blew hair out of the way, and was able to see inside a little better than before, although she had to twist her neck to let the sunlight in past her head.

“Do you see anything?” Now Danny was whispering.

“I can see four, no five figurines. They look like tin soldiers, kind of, but one of them is like a princess. I can’t…just a second.” She shifted her weight carefully, and lifted her right hand from the ground. She had to snake it between two buildings and under her left arm, and barely avoided knocking a hole in the central tower with her elbow, but finally she got her hand near her face. She lifted a lock of hair and carefully put it behind her ear, then, biting her lip, used a fingernail to pick at the hole through which she was peering, enlarging it. “There’s more. It’s like a ballroom. There’s, um, a priest, and there are words scratched on the floor. Can’t read them–”

The lock of hair fell in her eyes again. Exasperated, she blew it away again, but the puff of breath went straight into the interior, and disturbed a pile of chalky powder that had been deposited in the center of the floor. The powder swirled about and flew out through the gap in the wall and roof, right into her eyes and now-inhaling mouth. She choked for a moment, then began coughing helplessly, and immediately fell over onto the central building. She crushed it, feeling a sharp pain in her chest as it crashed through ceiling onto the ballroom tableau, and then the weight of the tower came down on her back and fell across the length of her. Her right leg shot out and took down other buildings and walls, and her left palm skidded and went right through another building and smashed painfully into one of the small boulders.

Still coughing violently, blinded by dust and dirt, she tried to roll to one side and get her mouth out of the dirt of collapsed buildings. She couldn’t breathe. She was beginning to panic when Loi and Danny grabbed her arms and lifted her out of the ruined castle. She couldn’t make out their frantic questions as the coughs racked her body, but she heard her brother exclaim when he saw the object projecting from her chest. She felt a tug, and then a weight bobbing between her breasts was gone, and then they had dragged her to the water and dunked her in. The water rinsed her eyes clear, and after a few moments she was able to master her cough reflex enough to drink a sip of water, then more, to clear her throat. But she wasn’t able to speak for several minutes; she just sat in the water, helplessly coughing and weeping, sometimes taking a drink, and choking it up as often as not. The boys comforted her, and after encouraging her to move her hand away, her brother checked the small wound on her chest. Her wrist felt slightly sprained from hitting the boulder.

As coherent thoughts came back to her, she began to cry in earnest. She felt ashamed–she had destroyed a thing of beauty and wonder, something magical, maybe even religious, for someone anyway. She saw herself for what she really was–an absurd, skinny, gawky child, ugly and awkward, acting like a whore, parading her flesh around a beautiful man who surely thought of her as nothing more than a foolish little girl, both he and her brother embarrassed at the display. They would be laughing at her, soon, laughing or, even worse, ashamed. She wanted to die. She wanted the Lake Monster to mercifully rise up and drag her away. She hid her face in her arms and cried and coughed and cried.

Finally, the tender words and caresses on her shoulders and head began to get through to her. “Maria, come now, Maria, mi hermana, don’t cry.” Loi and Danny were in the water beside her, holding her, cocooning her in their arms and bodies, their heads resting on her shoulders, words of affection buzzing in her ears. She stopped crying, slowly. They washed her face and lifted her up, took her up to the campsite and toweled her off, then lay her on her sleeping bag, in the shade.

Danny handed her a figurine. She sniffed and looked at him questioningly, not trusting her voice.

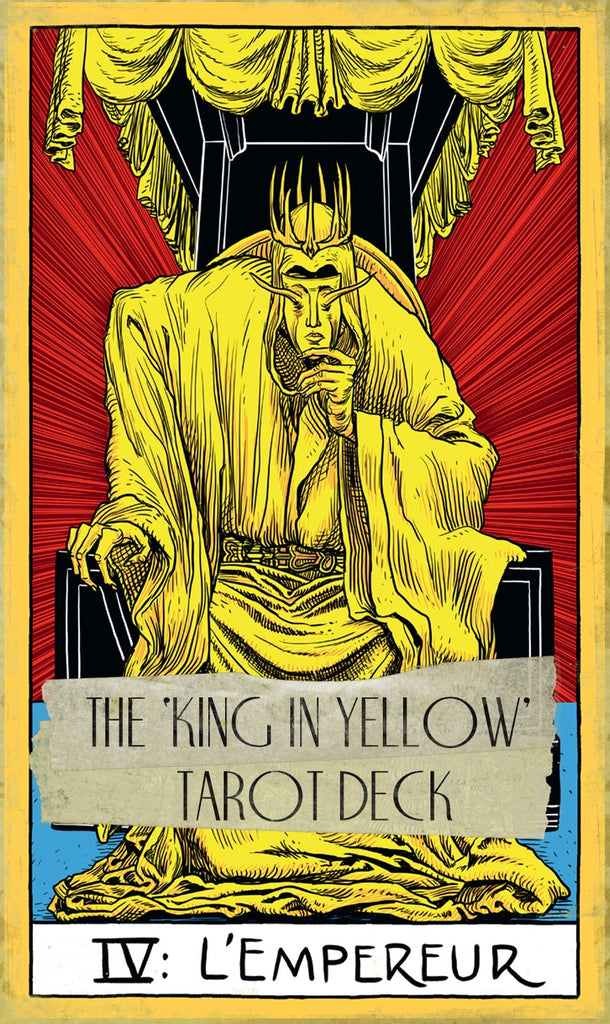

“You see this?” he asked. The figure was a baroquely dressed man, wearing a ragged yellow robe and a pale mask, holding a spear or staff. The tip was missing. “This was poking out of your chest when you stood up.” Her hand went to the wound between her breasts. It was a little dimple now, closed up. She felt a pressure inside, and thought the spear tip might be in there, perhaps even embedded in the breastbone.

Danny kissed her on the forehead and smiled sweetly. She smiled back, weakly. Then Danny left to join Loi near the shore, at the ruins of the castle.

***

They stayed there for some time, digging through the rubble. Maria got some clothes out of her pack, a T-shirt and some jeans, and panties, and went behind the Lake Monster Rock to change, in case they came back. As she took her top off, she felt a chill sense of being watched, and looked around in dread, covering herself. She saw nothing, and shrugged it off and dressed quickly.

She went back to the sleeping bag and examined the yellow figurine more closely. It was metallic, yes, but not tin as she’d thought. It was a little heavier than lead. It was painted in great detail, and measured about the length of her thumb. It seemed quite old, the paint chipped and worn away. The tip of the staff or spear was slightly bent and creased where it had entered her–something had clearly broken off, although it might have happened long ago. She decided not to tell Danny that she thought a piece of it might be inside her. She’d worried them enough.

On the bottom of the base of the figurine was a complex, tri-armed sigil, painted also in yellow. It made her think of an eye and a squid simultaneously, and she shivered as the air seemed to curdle around her. She set the figure aside and decided to shake off her morbid feelings by doing some work. She began gathering fallen deadwood for the fire.

The boys came back after a while, carrying with them all the figurines they could find. In addition to the yellow-ragged man, there were two princesses (nearly identical but clearly individual, on close examination), a regal-looking queen, a soldier or warrior, two princes, a priest, and someone who looked like a messenger, also wearing a pale mask that sometimes looked yellow, sometimes bone-white, depending on the light. Each had the yellow sigil on its base, each sigil hand-painted and so slightly different. In fact, Maria felt that the sigils looked different each time she saw them even on the same figurine, but it wasn’t something she wanted to suggest to Danny and Loi, after her bout of hysteria earlier.

They talked about the figures and the sigils and the castle, but came to no understanding. They set up the two-man tent and the one-person pup tent, got the fire going as dusk settled in, brewed up some coffee and wolfed down sandwiches and burritos.

Danny cleared his throat. “So, what do you think? Should we start the storytelling?”

Loi and Maria looked at each other doubtfully. Loi looked at Danny and said, “I think the day has been weird enough, no?”

Danny nodded. “Just what I was thinking, hermano. Tell you what–we’ve got three days here. Let’s put it off until tomorrow night.” They all agreed with relief. Surely by tomorrow, things would seem normal again.

But nobody wanted to go to sleep. They broke out the marshmallows and stayed up talking, chasing the bad vibes away by reminiscing about old times, Danny and Maria trying to top each other in coming up with more embarrassing tales about each other’s childhood. Loi was laughing loudly at a story about the time Danny was babysitting Maria and managed to get the cat covered with Elmer’s glue, when they all fell silent at once.

In the same moment, they all felt it. A fourth guest was sitting at the fire.

They tried not to look, but their eyes were drawn to him. He sat a little back from the fire, his face in shadow, the coal glow of the cigarette showing his tangled, matted beard, filthy grey and full of twigs and leaves. He wore a shapeless, broken-down hat that might have been a cowboy hat or a sombrero, and had a ragged serape made from an old horse blanket. His legs were stretched out so that, as far from the fire as he sat, his beat-up cowboy boots were almost in the fire. The left one had a hole in the sole.

No wind disturbed the fire or moved the trees, but they could hear a wind whistling, moaning, “UUUuuuUUUuuuUUUuuu.” Although it did not ruffle their clothes, it blew through their bones, their organs. They could feel it coming off the lake.

“Funny thing about lakes.” His voice was dead, ancient, deep as a turtle buried in the mud of a pond, hibernating through the winter. Reptilian. Croaking. Cold.

He stayed silent for a full minute–or was it an hour?–while they hung on his non-sequiter. They had no choice. They couldn’t move.

He shifted, and ash fell from his cigarette and dribbled down his chest. “Funny, I says. How d’you know what’s at the bottom? I mean the really deep ones, but even some u’ the reg’lar ones got nooks you’d miss thet go down further and further than anybody’d imagine. And how d’you know, really, whether they don’t all connect somewheres deep down?”

He took the cigarette and flicked it into the fire. The fire flared blue and green, then gradually shifted to a yellow that somehow felt unnatural, and pulsed but did not waver in time with the bone-vibrating wind. He pulled another cigarette from under his serape and leaned forward to light it in the fire.

If they were not paralyzed, they might have screamed. His face was diseased, horribly so. It looked as if made of wax, which had been heated so that it bubbled and ran, then cooled to preserve the disfigurement. Bone showed through at the nose, and a hole in one cheek showed teeth. The man leaned back, blessedly cloaking his visage in darkness.

He smoked meditatively for an age or a moment. “Mebbe they’re all one lake, deep down.”

He raised his hand and pointed toward the lake. “Look.”

Their heads turned. The lake was covered with mist. In it, they imagined they could hear the creaking of wagon wheels, the lowing of oxen, the crack of the whip. The jingle of sacks of gold, payroll bound for the mission and outpost garrison of San Antonio. A treasure train forever trying to reach its destination.

Their heads turned back to the man. He spread his fingers wide, then brought his hand down suddenly. “Sleep,” he said.

They collapsed, their strings cut.

***

She was in a party. It was the ballroom. Again, she wanted to scream. She lounged in a couch-like chair at a huge, three-winged, twisting table made from the rib-bones of one of the great beasts of the lake. She held a wineglass loosely in one hand, languidly slouching and decorously allowing one rouged nipple to peek out of her decolletage. She was smiling at her half-sister, Cassilda. Cassilda smiled back. They loved each other unreservedly. Each intended to poison the other, given a clear opportunity.

Everyone smiled. Her half-brother Thale (Loi!) smiled, pale and strained, his eyes full of agony. Her mother the Queen smiled. The priest smiled. Her brother Uoht (Danny!) smiled. There was a noise above them. A dry, chitinous rustling of wings. A plopping sound, as a rancidly yellow goo splattered all over one of the dishes on the mind-bending table. A hand-sized flake of dead skin drifted down to land on the floor. More goo plopped from the ceiling into the Queen’s drink. She ignored it, merely setting it down and taking up another among the many arranged around her plates. Servants, dwarfish creatures at whom it was difficult to look, whisked away the contaminated dishes and drinks within moments, but the foul rain continued to fall irregularly from the ceiling. No one looked up.

It was not good to look up.

Maria (Camilla?) thought furiously. This was just a dream. A terrible dream. She must, somehow, break free. There was a man by the fire. He could…do things to them as they slept. She had to wake up. Before the Messenger came. Before the Crime was committed.

A brazen gong sounded. The rustling of wings ceased, and a palpable sense of anticipation descended in waves from on high. Dancers came in, beautiful, delicate, veiled. They spun among the feasters as limpid music played, and the feasters laughed in delight. They laughed and laughed. They seemed unable to think of anything to say.

Something about the music awakened Camilla’s (Maria’s?) limbs. She carefully set down her glass, pushed back her divan, and rose, trembling. Cassilda laughed breathlessly, then stopped smiling, looking at her half-sister in surprise.

Camilla stood tall. She looked down at herself. Her hands were long and delicate and somehow wrong. Was there an extra joint in each finger? She couldn’t remember how many joints there should be. Her skin was porcelain white, with a touch of peach, that perfect Anglo complexion she had longed for as she’d gazed through fashion magazines (magazines?).

“Sister,” Cassilda said, with some alarm. “The gong announces a guest. Where could you be going now?” Her voice was musical and lovely and lacked some essential quality of humanity, and it made Camilla shudder.

Camilla’s throat would not open for a moment, but then she found her voice. “I would dance, sister.” And with that, she knew what to do. Again, her limbs moved of their own accord, not in the same dance she’d done among the mud-and-stone castle, but a new one, one that created a sort of syncopation with the music of the veiled dancers.

She could dance a path out of the dream. And she could take a partner, take someone up with her.

But only one.

She had to choose.

She chose Uoht (Danny! Danny, damn it!), of course. There was never any doubt. He took her hand, and as they danced, they wept, and kissed. As they spun madly among the veiled ones, they caught sight of Thale several times. She tried to tell him, I will come back for you. But she couldn’t speak. And she knew it was a lie.

Thale raised a toast to her, and his smile, for a moment, took on a hint of real feeling. Then she felt the huge doors swing open, and the soldier announced the arrival of the Messenger Yhtill.

***

She woke. She couldn’t move.

She struggled, and felt the pain of her overstretched joints. She was hog-tied, nude. The fire was dying. It was cold. The circulation was cut off in her wrists and ankles. Her legs and arms were behind her, and she had a noose around her neck that drew tight if she tried to pull her legs straight.

Loi lay across from her. He was also nude, bound. He was asleep. She heard a groan behind her. Danny.

A boot came down in front of her face. The diseased man squatted down before her. She kept her gaze on his boot. She didn’t want to see his face. His breath was unimaginably fetid.

“Came up out of it, did you?” He chuckled, a terrible, liquid thing. “Good. I’ll make you a Dancer yet, I will.” Things worse than lice crawled in his beard.

In a tiny voice, she asked, “Why did you make the castle?” Why not, What are you going to do to us, and why? She didn’t know. The castle just seemed more important.

He chuckled again. “I don’t make nothin’. I just shape it inta what it should be. Ex nihilo nihil fit, y’know. I’ll teach you that, I will. I’ll learn you ta dance the world inta new shapes.” He stroked her jawline tenderly.

There was a loud report, then another, two great cracks that made her jerk and half-strangle herself. The man’s head exploded over her, bathing her in blood and bone. His body spasmed and fell to the side. She could see a half-rotted tooth on the dirt before her, not four inches from her face.

Soft, cautious footsteps approached. A male shape loomed out of the mist, pistol held ready, double-handed, always pointed at the dead mass on the ground. This man, wearing a black sweater and jungle pants, prodded the corpse with a foot, examined the half-destroyed head, then seemed to breathe easy.

At the sound of her strangling, the man clicked on the safety of his pistol and slid it into a belt holster, then pulled out a K-Bar knife and quickly cut her ropes. His arms around her as she slipped free and began shaking with horror, she heard Hank’s voice, soothing, “It’s OK, angel, it’s all over. We’ll get you out of here, home, everything’s going to be fine.”

“N-NO! No, I’ve got to go back! Loi, he’s still in there!”

But the man just kept soothing her, then turned to her brother and Loi, and released them, too.

“Listen to me!” she cried, grabbing his sweater, unmindful of her nudity, of the drying blood and other matter covering half her body. “I’ve got to go back in! How do I go back in?”

He looked at her, confused. At her brother, also shaking in reaction, and at Loi, still out. A sort of comprehension dawned. He looked at her in awe and pity. “I don’t know,” he said, shaking his head. “I’m sorry.”

In the end, they could do nothing. Danny dressed and, stunned into a robot-like state, helped Hank drag the dead man’s bulk into the lake. They burned the clothes that the man has sliced off their bodies. Hank bagged the collection of figurines. Maria washed herself with canteen water, dressed, and tended to Loi, talking to him, trying to call him back up from the depths, begging him to awake.

There was no reaction.

***

Hank took them back to the Villanueva house, where he turned them over to the care of Mrs. Villanueva and had a long discussion with the Sheriff in his study. Then Loi’s parents came over and Hank talked with them. There was some shouting, then some quieter discussion. The Sheriff and Loi’s parents left to take Loi to the hospital. At the Sheriff’s request, Hank waited in the house, making a phone call behind the study doors. He then came out.

In the living room, Danny and his mother were asleep in each other’s arms on the sofa. Maria stood in front of the window, arms crossed, watching the sun rise. Hank stood behind her for some time before speaking.

“You were brave,” he said.

She shook her head.

“You were. I don’t know what happened, really, but I know this: if you had reacted like the average kid–hell, like the average adult–you and your brother, and Loi, would be dead now. Or worse.”

She gripped the windowsill, head down, jaws clenched.

“Cold comfort, I know. But true.” He tentatively touched her shoulder.

The sun was bleeding over the lip of the horizon. Their reflections began to fade in the window. She looked up, seeing them both there. She saw the pain in his face, and knew it wasn’t for her or Loi, but for someone she would never know. In despair, she choked out, “What will happen to him?” before collapsing into tears.

He sank to kneel on the floor with her, his arms enfolding her now. “I don’t know, angel. I really don’t know. But you’ve got to hope he might come back. You must hope. There’s not much that sets us apart from the others; I know that. Hope does. It makes us human.”

She fell into an exhausted, dreamless sleep soon after. When she woke, Hank was gone.

***

Daniel changed his mind and went to the University of Texas at Austin, majoring in Criminal Psychology. He joined the ROTC, as planned. Loi never recovered, remaining in a coma. His parents kept him at home after a few weeks in the hospital, and Maria helped than care for him. She sometimes got the feeling that Loi’s mother blamed her somehow, but that the woman fought against that emotion, and treated Maria like a daughter. Then, six months later, while everyone slept, Loi got up, dressed, slipped out of the house, and walked the four miles to Lake Espantosa. His clothes and shoes were found on the shore at their old campsite. They dragged the lake, but his body was never found. Several other sets of remains turned up, however, but Sheriff Villanueva had a talk with the coroner and the local reporters, and that part of the story never made the news, remaining nothing more than local gossip.

Soon after Loi’s death, Daniel transferred to the University of California at Berkley. He kept in touch with his sister, writing her long letters that she showed to no one, and she answered him in kind. They remained extremely close, sharing their thoughts and fears, with two glaring exceptions: They never spoke of that night at the lake, and they never spoke of Loi.

On her next birthday, Maria received a card with a Thai stamp and postmark, and no return address. The card was a simple folded piece of off-white, hand-made paper. On the front was scrawled the word “Angel.” Inside was a single Chinese ideogram, written with a brush in black ink. She took it to Loi’s parents. She hadn’t been to see them since shortly after the days of crisis when Loi had disappeared five months earlier.

Loi’s mother, an educated woman, told Maria that the character meant “Hope.”